|

While describing the fighting techniques in the body of the manual, it is difficult to fit in a discussion of the common ways in which these techniques are incorrectly applied. The following is an attempt to describe some of the common errors, and the ways in which they may be corrected. Most of them are concerned with a lack of power in blows. The problems discussed in this appendix are: :

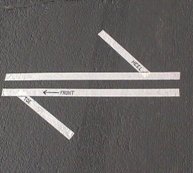

This is the most common error, and the one that is most damaging to the weaker fighter. This error occurs when both feet are on the line passing through the fighter towards the opponent. It is made worse when the feet are arranged in a modern fencing stance, Figure 19a) with the forward toe pointing to the opponent, and the back toe at a right angle towards the sword side. The effect of this is to prevent the hips and shoulders from rotating far enough to provide a full force blow towards the target. Unfortunately, this error has been, and continues to be taught as proper technique. This is likely because many men are sufficiently powerful in the upper body that they can strike a "killing" blow despite this error. Since it works for them, they teach others, even those fighters who do not possess enough upper body strength to overcome the error. The problem caused by this error can be corrected by using the proper stance described in the main body of the manual. (Figure 19b) As a reminder, both feet should be about shoulder-width apart, parallel, and pointing about 30 degrees towards the sword side of straight forward. (Figure 19c) Retaining this orientation, the back foot should be moved four to six inches towards the sword side. Check this by using a four-inch band (a 2x4 board, or the stripe in a parking lot) as the reference line pointing to your opponent. The toe of the front foot should touch the shield side of this line, and the heel of the back foot should touch the sword side. The back foot can even be one to two inches away from it. There is a proper point for everyone, but do not open your stance too much, since that will start to decrease the delivered power of your blows, even though it might feel better during the early part of the swing. If you completely open your stance, or even reverse your feet, several negative aspects enter the picture, including difficulty with returns, inhibited blocking to the sword side, and lack of support for the shield.

As stated in the body of the manual, in the on-guard position, it is important to have the sword elbow back sufficiently that the muscle in front of the shoulder is fully tightened. If this is not the case, (Figure 20a) there will be a delay in transmission of the power being generated by the body to the arm, because it will be necessary to tighten this muscle before the transmission can occur. In this case, the transmission will only occur when the body has rotated enough that the muscle becomes tight. If the arm is allowed to move as the body rotates, the muscle will never tighten. During this delay, some power will likely be lost. If the departure from proper form is great enough that the sword hand, and even the sword arm are in front of the shoulder during the on-guard position, a significant amount of power and speed will be lost. Again, the correction is to train yourself to properly position your sword arm. As a reminder, (Figure 20b) the sword hand should be just above the shoulder, and close enough to the head that you should be able to touch your ear if you extend your index finger. The hand should be palm-forward, or any place from there to palm down. The former hand position provides more variety in initial blows. The latter provides a bit more speed. The sword elbow should be back far enough and held high enough to completely tighten the muscle in the front of the shoulder. It is not a particularly natural position, but can easily be assumed, and reasonably easily held after some training.

This is another very common problem. This occurs when the fighter swings the sword without supplying the main power from the rotation of the body and the drive of the legs. Thus deprived of the majority of its power, the sword does not hit as powerfully as it could. In addition, the focus of the sword strike is turned from a strike to a point, with the uncoiled power of the body behind it, to a swing through a point, with only the arm supplying power. Powerful fighters can get away with this, and therefore tend to teach it as proper technique. This is unfortunate for any of their students who lack the power necessary to deliver a "killing" blow with their arms alone. However, improper technique, especially while moving during the combat, is the more likely villain. The two items below are the most common of these.

This is the situation that occurs if your on-guard position is one in which your chest points directly at your opponent, as in Figure 21a. It is possible, although difficult, to do this even with the feet and hips in the proper position. This eliminates the power provided by the back, chest, and shoulder muscles to the swing. It also eliminates about 45 degrees of arc through which the sword hand and shoulder would move, gathering kinetic energy all the way, if the shoulder were started from the proper position - about 45 degrees (or a bit more) from the line of advance. (Figure 21b) To correct this, make a point of checking your shoulders when you assume the on-guard position before, or during a pause in a fight. Watch for this in your practice partners.

This is the situation that occurs when you fail to return your shoulder to the proper position between swings. (This does not mean that you must stop there, just that you should pass through the proper point.) This occurs most often during movement, either forward or to the side. Figure 22a through Figure 22c show a swing from a proper on-guard position, with an improper return, where the sword is not returned far enough. If Figure 22d is substituted for Figure 22c, the return is correct.

The type of blow described in the body of the manual is a snapping, whipping blow. It is designed to produce a lot of force that is delivered to the target during a very brief contact. This is the type of blow used to break armor. If you step forward (especially if it is with the sword foot) while you are swinging your blow, you will increase the time that the sword is in contact with the target. This spreads the energy being transferred over a longer period of time. This causes the blow to be more of a push, and your opponent will not feel the crisp contact necessary for a "kill". It is correct to step forward just before you initiate the strike, but not during it. If a step with the sword foot must be taken, the step must be taken before the hip starts rotating. Both pell work and slow work as described in the manual are useful in correcting this. The problem can be subtle, so an observer may be helpful.

This situation occurs when you are in too much of a hurry to get to the next swing, so you don't move your sword back far enough during your backswing. This does not allow any of your muscles to contribute sufficiently to either the backswing or the subsequent blow. Nor does it allow the sword hand to travel through enough of an arc to pick up much kinetic energy. The result will be blows of diminished power, and very predictable swings, which all come from the same point. The incorrect return is shown in Figure 23a through Figure 23d.

The correct return is shown in Figures 23e through Figures 23h. To correct this, you must develop the disciplined habit of keeping your sword moving, and not returning to your shoulder, between strikes. There are two very good methods by which this can be accomplished. The first is to do pell work, preferably with a mirror, and constantly remind yourself (or have an observer assist) to move the sword as far to the rear as possible during the backswing. The second, and more important, is to practice using the disciplined slow work described in the body of the manual. Once you have learned how to do this type of slow work well enough that you don't need to think about it, you can start paying attention to specific aspects of your technique - like moving the sword as far to the rear as possible during the backswing. Note that all circular motions (like a sword swing) contract towards the center of rotation as the motion speeds up. Therefore, the motions used in slow practice should be moved further out from the center of rotation than they would be for a normal-speed motion. This can be observed particularly in Figure 23g, where the backward movement of the sword is greater than it would be if performed at full speed. If the slow practice movement is practiced in this manner, the full speed blow will move through an optimum path. If the slow practice movement is abbreviated as in Figure 23c, the resulting full speed motion will be unacceptably short. This is the situation in which you return your sword to your shoulder, as in the on-guard position, briefly between your swings. There is no necessity for doing this, and it both decreases the frequency of your swings, and it will likely reduce their power. The reason for the former is obvious. If you stop, however briefly, during your backswing, your next swing will not arrive as soon as it would have. The reduction in power will likely occur because you will probably not have returned your body to the proper on-guard position, with the hips and arm properly positioned, when you stop your sword. Therefore, you will not be fully set to initiate the next blow. In summary, stopping loses the power that might have been carried over from the backswing, and encourages you to not have your arm and hips fully cocked for the next blow. Both pell work and slow work as described in the manual are useful in correcting this. Ask your training partners to point this out to you. The concept of "commitment" was discussed in the body of the article. In this context, commitment refers to a disposition towards a particular movement or direction of movement. Such commitment should be avoided because it can be used as a cue by your opponent to determine what and when you are going to do next, or to determine that you are out of position to counter a specific attack. In addition, leaning in any direction has the unfortunate effect of committing you to movement in that direction. It does not mean that you have to complete the movement, but it does mean that you have committed to it. However, if you do not actually make the movement, you are forced to expend extra time and energy to return from that commitment (the direction of the lean) to a neutral point, before moving in another, desired direction. In most cases, anything that forces a commitment of this sort is to be avoided. There are plenty of fighters who can take advantage of these unintentional commitments to hit you one way when you are committed to another. There are special circumstances in which some sort of lean provides an advantage. This advantage, however, likely does not apply to most situations. If you are going to lean to gain an advantage, be sure that the situation is correct for you to achieve something with it. Also remember that there is no such thing as a free lunch. For every advantage, there is a price. When you lean, you pay the price described below. If you gain no corresponding advantage, you are paying too much. Leaning inhibits the rotation of the body, so it can negatively affect power generation, and blocking range, reach, and speed. In addition, leaning limits the options for throwing blows. Both pell work and slow work as described in the manual are useful in correcting this. Ask your training partners to point this out to you. 8. PUSHING BACK WHILE SWINGING Figures 24a through 24c show a swing with the problem occurring. Note that during the swing, the knee moves back from its original position, pushing the body back as well.

This is another very common problem that significantly reduces the power of blows, and interferes with the backswing. It is caused by pushing back with the front leg while swinging a blow. In severe cases, the leg actually straightens, but usually the leg remains bent. In either case, the hips are pushed back as the sword moves forward. The power of the blow is reduced because it loses the drive of the back leg, and is deprived of the impetus provided by weight of the body moving forward and slightly down. The backswing is greatly inhibited because the front leg is what drives the backswing. The backswing is executed in a manner that is similar to throwing a left-handed blow towards your sword-side rear. The front leg must drive the hips around towards the sword side and back. If the front leg is straight, or has pushed back to the shield side, it is very difficult to get any drive from it to support the backswing. This problem often contributes to Problem Nine - Pulling Returns Into The Body.

Figures 24d through 24f show the correct swing with the knee remaining bent, and some weight being shifted forward. Note that the center of balance does not move forward when the weight is shifted, although the shoulder and hip rotation in Figure 24f do move that side of the body forward. Everything balances. The sword shoulder, sword hip, and shield knee move forward. The shield shoulder moves back, and serves as a counter-balance. Again, the correction can be achieved with pell and slow work. Pell work can be especially productive if you can do it with a mirror. The mirror should be placed so that you can look sideways into it. When it is in that position, the mirror can more easily show whether or not you are pushing back.

Figures 25a through 25e demonstrate a side-return with the problem occurring. Note in Figure 25b that the sword is being pulled back too close to the body. In Figure 25c, this continues, resulting in the hand moving between the elbow and the body. The sword is now trapped. The only recourse is to whip the sword around horizontally, causing the blade to move behind the body towards the shield side. Figure 25f shows Figure 25c from the front. This is a subtle, but very serious problem. While performing a backswing, it is important for several reasons to keep the handle of the sword moving back towards a point outside of the elbow. If, instead, the handle moves back, but towards the body, the elbow is forced to move out. This has the effect of "trapping" the sword between the arm and the body.

Once this happens, the only ways to free the sword are to either move it forward then to the outside, or whipping the sword out and back. Moving the sword forward to free it is difficult, since this problem most often occurs when your opponent is advancing, and there is little time available to "reset" your backswing. The second method of freeing the sword, that of whipping the sword out and back, requires considerable forearm and wrist strength, and moves the sword into a horizontal path. This, in turn, causes the sword to move horizontally across the back towards the shield side, causing considerable wasted motion and time, and limiting the options for the next blow. Generally, once you have trapped your sword, you can free it only by moving away from your opponent, having had to block several of his or her blows without response. The problem is generally caused by two technique flaws acting together. The first of these is leaning forward. Strong hip and shoulder rotation are necessary for the side return, which requires the sword to move down, out, and back. The leaning interferes with this by inhibiting the rotation of the body. The second of these is Problem Eight - Pushing Back While Swinging. In addition to reducing the power of blows, this technique problem (number eight) also interferes with the backswing. When the front leg pushes back, the hips are forced back, usually causing the shoulders to lean forward. This not only interferes with rotation, it stops it cold. Then, when the sword arm tries to move back, the path of least resistance is towards the body. Another contributing factor is Problem Eleven - Poor Range Control. Specifically, if you get too close to your opponent, such that your shield is pushed back into you, your legs may move slightly ahead of your body, causing a slight lean to the rear. The backward lean is often avoided by leaning forward. In either case, you are leaning, (or perhaps also pushing, which is an even greater commitment) and the rotation of your hips and shoulders is inhibited. You are then back to the start of the previous paragraph. It is difficult to correct this problem. The best method is pell work, with attention being paid to the knees and to weight shift during techniques. The knees should bend and unbend during techniques, but they should never straighten. During swings, the weight should shift slightly towards the front knee as it bends and moves slightly towards the shield side. On the backswings, the weight should shift slightly towards the back knee, causing it to bend and move slightly towards the sword side. The movements of the knee should be timed to accentuate the motion of the hips. Continue to pay attention to the knees and the weight shift during slow work. Another method of practice that can help in correcting this problem is to watch your sword during the entire course of the backswing. (It's useful, but not necessary, to use a mirror.) Swords will move any way that you want, if you move them slow enough, and you watch them. If you have a mirror available, watch your reflection from the front and from the sword side. The different views will allow you to see, and correct, different aspects of the sword's motion. In addition, practice the proper side return technique, especially using the exercise described in the body of the manual.

Figures 25g through 25k show a correct side return. Note in Figure 25h that while the sword is being pulled down, it is also being pulled slightly out from the body. In Figure 25i, the hand and the entire sword are outside of the elbow. Figure 25l is a front view of Figure 25i.

10. ABDOMEN NOT TENSED PROPERLY This is actually a problem in the timing of force application during a swing. It usually afflicts fighters who have a Karate background, or who have a very flexible waist. The situation occurs when the hips are rotated too quickly during a swing, without allowing time to transmit the drive force from the legs. This reduces the power of the blow being struck. The reason that it affects ex-Karate players is that in Karate the weapon being moved is the hand, which weighs much less than the sword. In that case, a more powerful whip is produced by a faster hip rotation that pulls the hand after it. With the much heavier swords, the hip rotation needs to be much slower, so that the drive from the leg and the rotating body can act on the sword throughout the first half or two-thirds of the swing. Similarly, those with a very flexible waist tend to rotate the hips quickly without the slower tensing of the abdominal muscles required for proper timing.

Figures 26a through 26c demonstrate the problem. Note in Figure 26b that the lower end of the tape lines on my abdomen have already moved around to my left, while the upper ends of the lines, and the sword shoulder, have not yet moved. Contrast this with Figures 26d through 26f, below, where the ends of the lines move nearly simultaneously, just very slightly in front of the sword shoulder. In many cases, the problem is worse than is shown by the illustrations. I am not especially flexible around the waist, so I could not demonstrate the problem well.

The "butterfly walk" and the return exercise are useful in correcting this problem. Practice in slow motion, so that you have time to notice what you are doing, and to correct it if necessary. The proper technique is to start tensing the stomach muscles as the hip rotation starts. Both the tensing and the rotation must be gradual, reaching completion just as the sword hand leaves the shoulder. The hand, of course, is the last thing that moves during the swing. All things being equal, the best distance at which to fight is the distance that allows you to perform your techniques easily. However, things are rarely equal. My strategy has always been to fight at the distance where my techniques were more effective than my opponent's. My techniques are best and most extensive at normal sword range. However, if my opponent also likes that range, I may move outside or inside, depending on which range best suits me, and least suits my opponent. For instance, if my opponent has a super-speed snap, the last thing I want to do is to fight from outside, where my lack of speed puts me at a disadvantage. If my opponent is taller and heavier than I am, fighting at close range is likely not a good option. For instance, I once had the experience of fighting Duke Uther with bastard swords. My normal technique with that weapon is to fight very close. My inside techniques are very good, and I am usually at least as powerful as my opponent. This was probably true in this case, but, his Grace is five inches taller, and at the time was several dozen pounds heavier than I. I found myself in the position I preferred, but with his Grace's forearms on top of mine. This made it difficult to perform my techniques. After backing up about one foot, things started working again. Generally, the better fighters have good outside and inside techniques, as well as those for the middle distance. Unless you know that your opponent has a weakness at a specific range, take the one that works best for you. One thing that may be of use is a technique of safely crossing over the "in range" line. I have found that the technique that works best for me is to lead with my sword, while swinging at my opponent's weapon. This has two advantages. The sword crosses the line first, and my swing interferes with my opponent's weapon. Leading with one's head is what I call the "Rocky Balboa" style. Leading with your shield is not as bad, but it does commit your shield to a horizontal, forward motion. This is not useful for blocking blows to the head or leg. The trick is not to step before you swing, but to let the swing pull your back foot into a step as your sword moves away from you towards your opponent. This will lessen the effectiveness of the swing, but it will get you in range, with your weapon moving, safely. I usually follow up this swing by quickly moving my shield towards my opponent's weapon. The preceding paragraphs are tactics. The problem that I wish to discuss here are those caused by getting in too close. If you move quickly to the inner range, and get so close that your shield is pushed into you, several things can happen, all of them bad.

The leaning can, in turn, contribute to Problem Five - Short Return, Problem Eight - Pushing BackWhile Swinging, and Problem Nine - Pulling Returns Into Body.

|